Book Reviews by Uri Geller for the Jerusalem Post

November 2000

True stories about liars

Imposters : Six kinds of Liar by Sarah Burton. London, Viking/Penguin. 246 pages £15.99

By Uri Geller

The imposter, someone who claims to be an utterly different person, is the essence of cinema. This concept is  superbly grasped by historian Sarah Burton, who has filled her study of make-believe princes and cross-dressing doctors with a panorama of vivid images.

superbly grasped by historian Sarah Burton, who has filled her study of make-believe princes and cross-dressing doctors with a panorama of vivid images.

The attention-grabbing picture – with which she chooses to open her show is of a top hat, floating on swirling water.

The water eddies, but the hat does not move. It is clamped to a head – a top hat worn by a submerged body, bolt upright in the river.

The body was of Harry Stokes, a hard-working bricklayer – except that Harry Stokes, as the Coroner’s Court

discovered, was a woman. Harry was born Harriet, but throughout “his” life, during a brief marriage and then a long relationship with a widow who ran a pub, the coarse-mouthed, pipe-smoking imposter was never discovered.

Burton works in vignettes, brief and vivid images painted over a handful of pages. Again and again she leaves the reader longing for a full biograpy devoted to any one of her subjects.

Louis de Rougement’s tale is told at some length. This 19th century bankrupt and wifebeater concocted an extraordinary autobiography of his life among the Australian cannibals, who treated him as a god. His quick invention and readiness with a concealed stiletto saed his life in numberless adventures – we see him “standing on the back of an enormous alligator, and tugging at my tomahawk, embedded in it’s head,” before his native wife thrusts a paddle down it’s gullet and Louis, “drawing my stiletto, blinded him in both eyes, afterwards finishing him leisurely.”

For months this hybrid of Robinson Crusoe and Tarzan was the toast of London, though genuine explorers poked holes in every part of his tale. He was believed, because people wanted to believe.

Brian McKinnon, the 31-year-old schoolboy is dealt with more briefly. During the Nineties, calling himself Brandon Lee, he returned to the Scottish school he had left 13 years earlier, and persuaded the deputy rector he was a 17-year-old from Canada.

Teacher Gwyneth Lightbody said staff and pupils convinced themselves he was “an old-looking, odd-looking

teenager – an alien from Canada – rather than an adult who looked his age.” They preferred to suspect he had an ageing disease, rather than that he was simply a liar and an imposter.

“We were a right crowd of dopes,” she said. “He stood out like a sore thumb.”

My favorite tale concerns the outstanding medic of the Napoleonic era, Dr James Barrie. Argumentative and sneering, he made enemies wherever he worked. During the Crimean campaign, he forced Florence Nightingale to stand in a blisteringly hot public square and endure an unprovoked tirade. She later called it the worst tongue-lashing she had ever suffered.

No one knew Barie’s precise origins, though it was whispered he was the illegitimate son of a nobleman. Illegitimate he was, but a son he wasn’t – Barrie was a woman, and a woman who had also been a mother. Like Harry Stokes, he carried his secret to the death. That is, she carried her secret…-

June 2000

The Secret History of Ancient Egypt

by Herbie Brennan, London, Piatkus,

218 pages. £16.99

Reviewed by Uri Geller

The pyramids of Egypt are the greatest mystery on Earth. The greatest in size, the greatest in mystification. The most jaded, shallow tourist will gaze on these vast outcrops of Bronze Age geometry and murmur, “How could that have been done ?” The more we learn, the more we are mystified.

Flinders Petrie was no cynical sightseer – 120 years ago, this young Egyptologist was bringing the precision of civil engineering to archaeology. He showed that the base of the Great Pyramid at Giza was utterly flat – a ripple of no more than one quarter of an inch across the whole, 13-acre surface.

He also proved the builders, 4500 years ago, sawed and drilled the granite inside the King’s Camber. This seemed impossible, since bronze is a soft metal and granite a very hard stone. Could the saws have been diamond-tipped, mused Petrie ? And what could explain the depth of the drill bores, suggesting two tonnes of force were powering the diamond bits ?

No human could exert such force. Only machines could do this.

Herbie Brennan collects dozens of these teasing facts in his book, subtitled “Electricity, sonics and the disappearance of an advanced civilisation.”

He fins images carved in stone of what appear to be a helicopter, a submarine, and a delta-wing jet. He shows how, if the Great Pyramid’s four corners touched the equator, it’s tip would exactly reach the North Pole.

He describes how 11 white-robed, chanting priests in Poona, India, were able to lift a 40-ton rock with only their fingertips – perhaps by creating a sonic field which caused the boulder to levitate – and asks whether the immense stones of the Pyramids were transported this way.

This is the kind of book that sets me telephoning friends and photocopying pages to pin on the wall. “Listen to this, read this – can you imagine that was possible ?”

It’s a rag-bag of thrills, lacking a strong narrative structure, constructed mainly of glittering gems of parascience plucked from other writer’s books, but Brennan has still achieved something unique. No other pyramid study – and there are dozens – has ever rounded up so much weirdness.

Here is Nikola Tesla, transmitting electricity through the air like TV pictures (did the Egyptians possess this technology ?)

Here is Nina Kulagina, the Russian pychic, moving objects with the energy field around her body (was psychokinesis highly developed among the Egyptians ?)

Here is Professor W. G. Burroughs, finding fossilised human footprints 300 million years old (long before the dinosaurs died out – did the Pharoahs know secrets of human history dating back to the era of Tyrannosaurus Rex ?) Every answer poses 20 questions.

Such as, why did a people capable of breathtaking engineering on a heroic scale, never invent an easier form of  writing than to carve pictograms into stone ?

writing than to carve pictograms into stone ?

The reviewer maintains the following website : www.urigeller.com

December 31, 1999

Parascience Roundup

by Uri Geller

It sometimes seems to me that the 20th century has been someone’s nightmare – a bad dream, where every reality turned to toxic dust in the dreamer’s fist, and every scene segued inexplicably into a wildly different landscape.

A century without continuity, without logic, without meaning, without pity.

Who dreamed this? What kind of man could endure a paranoid acid trip as mind-blistering as the past 100 years? From the brevity of E=mc2 to the immensity of Hiroshima, from a single bullet at Sarajevo to a million dead in one day on the Somme, from a sick mind spewing the doggerel of Mein Kampf to six million slaughtered in death factories, and from an on-off switch toggling in a binary computer to a network combining all the information on the planet.

There has been only one mind in all history which was weird enough, callous enough and brilliant enough to imagine the 20th century. That mind belonged to Nikola Tesla. Though the world has forgotten him, this Serbian scientist invented alternating current electricity, radio and the fluorescent light. He may also have designed a death ray, discovered a way to transmit unlimited electric power through the air without cables, and solved the question of what gravity is.

THE MAN WHO INVENTED THE 20th CENTURY by Robert Lomas

Reviewed by Uri Geller

(London, Headline; 248pp.; £12.99) is Nikola Tesla’s story. It is the most extraordinary biography imaginable, the tale of a lonely boy who was disdained by his parents, who fled to America to make his fortune and became Thomas Edison’s most brilliant engineer. Edison was a showman who guaranteed himself renown by inventing the photograph and the electric lightbuib. He also

devised the first major electricity supply system, using direct current.

Direct current was inefficient and could be transmitted for only a few miles. And Edison had staked a fortune on it.

Tesla had perfected an invention in his mind which would wipe out direct current: the alternating current motor. It is a measure of his genius that this machine, generally believed by engineers to be impossible, worked just as it did in his head – flawlessly. But it is also a measure of his extreme lack of business acumen that Tesla took his invention to the one man on the planet who would most wish to see it destroyed – Edison.

The pattern repeated itself throughout his life. George Westinghouse bought Tesla’s patents off the inventor for a pittance, and founded an electric company which soon powered America.

Marconi reaped the reward of inventing radio, though Tesla had proved years earlier that invisible waves could carry sound across continents.

The invisible waves could even carry electricity, though the idea of free energy for all has never appealed to power companies.

Tesla’s eidetic imagination, able to picture every part of a machine from every angle, was only one factor in his extraordinary personality. He never married, being unable to bear the idea of physical closeness to anyone. He would claim to have a chronic skin complaint to avoid shaking hands, and washed compulsively, always drying himself with fresh towels. Yet rather than compromise his vision and work with Edison on a DC power supply, for a year Tesla dug ditches for a living.

Robert Lomas’s storytelling is sometimes pedantic. But the tale of Nikola Tesla is so incredible

that it soars above the stolidity of the writing. Tesla proved parascience was real science, and created the 20th century. But if all this has been his dream, we must pray that his reveries bring hope instead of horror in the 21 st century.

FOR YOUR sake, reader, I hope I am not an idiot. But I am becoming addicted to a series of bright orange books called the Complete Idiot’s Guides. Three on my desk are titled JEWISH HISTORY AND CULTURE, TAROT AND FORTUNE-TELLING, and THE COMPLETE IDIOT’S GUIDE TO BEING PSYCHIC by Lynn A Robinson and LaVonne Carlson-Finnerty (New York-, Alpha Books; 408pp.; $18.95).

Page 294 of the Guide to Being Psychic reveals the secret of spoon-bending, which is a great relief to me since it means other people can take over the onerous duties of mangling the planet’s cutlery. One accurate observation suggests novice spoonbenders will have better success when the audience is on their side. Positive, open minds are great for psychokinesis – negative, skeptical minds are not.

These books are crammed with easy-to-use features, packed into short spurts of text and peppered with quotes, asides and definitions. The Jewish History guide, written by Rabbi Benjamin Blech, is a thorough overview of our nation’s past and its people. And it’s hilarious too. I am not a seer – when I glimpse other people’s future I usually keep what I’ve seen to myself – so the introduction to Tarot by Ariene Tognetti and Lisa Lenard was crammed with information I had not encountered before. I recommend these Guides.

I wouldn’t want you to imagine that I am lumping Professor Richard Dawkins with the Complete Idiots, but I have just read the paperback imprint of UNWEAVING THE RAINBOW by R Dawkins (London, Penguin; 352pp.; £8.99). To disprove the concept of psi-power, he uses statistics to demonstrate that watches are always breaking down and starting up, regardless of whether “an imaginary psychic” (i.e., me) is appearing on television. Dawkins confesses he is guessing at the statistics. Fine – I can set him right with the real figures.

Instead of the half-dozen phone-calls he anticipates from viewers who have witnessed psychic phenomena during my TV specials, he can revise his estimate upwards – about 35,000 per

cent. A total of 2,000 callers is not unusual for my shows.

He prefers his rainbows unwoven. And, in their separate strands of shimmering raindrops, rainbows are fascinating. But he ignores the fact that rainbows do not naturally exist in tiny pieces. They are whole. They are one. Their colors rely for definition on each other. A single shiny raindrop is pretty – a billion are awe-inspiring. Dawkins tries to make the rainbow a metaphor for

science. In fact, it is a perfect metaphor for the oneness of humanity. Singly, as selfish genes, we are interesting – interesting enough to satisfy the professor. But in our billions, like a rainbow, we are magical.

Uri Geller’s novels Dead Cold and Ella are published by Headline at £5.99. Mind Medicine is published by Element at £20. Visit him at www.urigeller.com.

PARASCIENCE ROUNDUP

by Uri Geller

THE LONG BOOM by Peter Schwartz, Joel Hyatt and Peter Leyden. London, Orion Business. 288pp. £20.

I’m an optimist. But am I optimist enough to think that I’ll live for 1,000 years?

I am a telepathist. But do I believe I will ever use telepathy to talk to my computer?

The Long Boom theory of economics says my chances are looking very good. Not just my chances, but the future of at least half the world’s population, including hundreds of millions of people currently mired in the planet’s direst poverty.

Within 20 years, according to Long Boom thinking, three billion people could be part of the global middle classes, with access to medical care, good housing and limitless electronic communications networks.

Gene repairs will make their bodies endlessly renewable, beyond the reach of death. Brain implants will connect their thoughts to the Internet.

War is over, disease and starvation are defeated, the environment is safe. That’s the Long Boom.

It sounds much too good to be true. And even the theory’s inventors, three Californian dreamers, admit it isn’t true; not yet.

But for the first time in history, we have the potential to create Heaven on Earth. Futurist Peter Schwartz, a 53-year-old economics analyst who first propounded the Long Boom in a 1997 magazine article, says: “I’m not making a prediction. I am merely saying that things have the potential to be this good if we don’t screw them up.”

Schwartz, the son of Auschwitz survivors, was born in a post-war relocation camp in Germany. His reputation as a business seer soared when, as a Shell analyst, he helped the company make billions during the oil market crash of 1986.

Journalist Peter Leyden calls their theory a “meme” – “a contagious idea that can quickly spread around the world and influence what people think and do.”

And this is a powerful meme, because it is so positive, so upbeat.

It’s the kind of idea which, the minute you have grasped it, makes you want to call friends and explain it to them. The concept is a enough to make anyone smile – “it’s laughable, and yet it seems so plausible, so possible. If only …..”

Some of the main ideas are:

Technology: Within half a century we will use Ideas Tools, radio chips embedded in our minds to project our thoughts to computers built into everything around us – all of them online.

Ecology: Competition and consumer pressure will force producers to build clean, sustainable factories.

Capitalism: With knowledge and innovation as the currency of the future, everyone will invest in themselves, by acquiring education and tapping into global communications.

Energy: Fossil fuels will be replaced by powerpacks that create no pollution.

Famine: Genetic engineering will develop wonderplants to feed the planet.

War: When all the world is a single, wealthy market, without trade barriers, war will be unthinkable.

Feminism: Women and children worldwide will achieve equal status with men as the information society spreads.

Health: The current generation of adults can expect to live to 120. Our children might even hope to be enjoying life in the 31st century. And people with a 1,000-year lifespan will have a massive stake in world peace and global ecology. Schwartz emphasises that economics is not a drug like Ecstasy. Four decades of buoyant financial markets will not make every single person loving and kind.

“I’m not talking about a perfect world,” he insists.

“There will still be unhappiness, broken marriages, crime, death and taxes, But I am talking about a safer, better, more prosperous world than the one we have now.

“The Long Boom is not a prediction. It’s a first draft idea, with the emphasis on “first draft.”

For this new era of hope to dawn over the whole planet, we must all play our part. We can all think positive, if we have the courage. We can all be optimists, if we dare.

It’s a great idea, a mesmerizing meme. Now it’s over to you.

THE MEME MACHINE by Susan Blackmore.

Reviewed by Uri Geller

Oxford University Press. 264pp. £18.99.

Meme theory says ideas are like genes: only the best survive. Think of an idea as being a thought-virus – it spreads from one brain to others, overpowering and dislodging old notions and mutating as it goes. One mind adds a twist, another injects a dash of new life..

But unlike genes, memes can be killed off by a single mind which generates a counter-meme. Think of the worldwide belief that God created the world a few thousand years ago – killed off by Darwin’s idea that life has evolved over hundreds of millions of years.

Darwin’s memes belong at the front of this argument, because the word was coined by ultra-Darwinist Richard Dawkins. But my favourite explanation of the idea appeared years ago, in a study of the Arabian Nights stories by Robert Irwin (published by Alien Lane in 1994; 344pp; £20).

Irwin argued that stories were alive. The best hopped from mind to mind and survived for thousands of years, with embellishments and alterations. They survived, using human brains as hosts, like benign viruses. I loved the thought that stories had lives of their own, and belonged to us only as long as they lived solitary and unspoken in our heads. As soon as they escaped, they were no longer the property of a single mind – they belonged to everyone who heard the tale … or they owned every listener ….

Blackmore misses the romance of this idea. She is fixated on the scientific nuts and bolts of memetic reproduction, rather than the mystical immortality of tales and ideas. But the central theme, that we are all meme machines which evolved as propagators for ideas, is wonderfully controversial.

Humans have no intrinsic value, she implies – we are only as good as the ideas we spread. We were invented to help ideas travel, just like fax machines and books and the Internet. We are

human telephones, born to breed thoughts. If Dr Blackmore is simply a machine, I have to concede that she is firing on all eight cylinders.

Uri Geller’s novels, Dead Cold and Ella, are published by Headline at £5.99. Mind Medicine is published by Element at £20. Visit him at www.urigeller.com

Friday November 26, 1999

An Alternative View

Reviewed by Uri Geller

The problem with the paranormal is that it’s so weird. Most people seem willing enough to believe the evidence of their own eyes when they see a spoon bend. But often, within a few minutes, they begin to discredit what they’ve seen. They fear that if they start believing in the paranormal, they are going to be waist deep in hogwash. Psychics all spout such a fountain of nonsense.

Nonsense about aliens, for a start, come to snatch us in our sleep and spirit us to space-ships for creepy sexual experiments. Nonsense about health, like homeopathy, the weird idea that water remembers the medicines which once washed through it.

Nonsense about alchemy and the ludicrous notion of turning lead into gold. Nonsense about clairvoyance, as though anyone could close his eyes ahd mysteriously see some place hundreds of miles away.

But if it’s all nonsense, why is a Harvard professor of psychiatry convinced that alien abductions are a real phenomenon, revealing a vital rnechanism of the mind? Why is Nobel Laureate Professor Brian Josephson, head of the Cavendish Labs at Cambridge University so enthusiastic about theories that water has a chemical memory ?

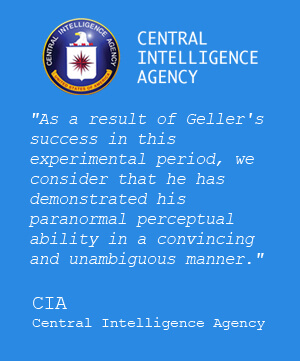

Why did the greatest scientist in history, Isac Newton devote so much of his time to alchemy? And why did the CIA fund a massive psi-spy program called Stargate, training psychics to “remotw” view enemy installations?

Some of the world’s most brilliant brains and most powerful organizations have torn up their prejudices and opened their minds to the paranormal. Now you can do the same, with the publication of four ground-breaking texts.

ALIEN DAWN by Colin Wilson. London, Virgin. 322pp. £16.99.

Reviewed by Uri Geller

Colin Wilson is Britain’s best known popular philosopher. His knowledge of the mind’s dark side is unrivalled, whether he is defining the rebellious, antisocial urges that drive great artists or documenting the evil sprees of serial killers. He admits he took little interest in UFOlogy before meeting John Mack, professor of psychiatry at Harvard, who believes electrical frequencies in the brain could determine what we are able to perceive. After years examining alien abductees – sane but distressed people who believed they had been visited and medically tested by nonhuman creatures – Mack concluded that altered states of consciousness might act as sieves of varying sizes. One sieve would take some data from the world and let other information slip through But a different sieve would pick up different data – and capture a different reality.

Horrified and fascinated, Wilson launched himself into the most wide-ranging study of the subject ever attempted. His wry skepticism keeps the evidence credible even when he is describing nightmares of mutilated animals and demonic possession. There does not yet exist any clear theory which explains all aspects of alien abduction. But Wilson, in a calmly scientific way, has laid bare all the terrors of its victims.

THE MEMORY OF WATER by Michael Schiff. London, Thorsons, 164pp. £14.99.

Reviewed by Uri Geller

Jacques Benveniste, director of the Digital Biology Lab in Clamart, France, believes his team can sample and record the effects of drugs, antibodies and bacteria on a computer, like musicians sampling sounds. The biological “noises” can be stored on disc, transmitted around the world, and replayed – and a human body will react in exactly the same way to e-drugs as, it does to real drugs.”

“The signature of a virus can be recorded and digitized using a computer sound card,” he

says, just like an ordinary sound” The implications for medicine are limitless. Rare serums will be sampled, copied a rnillion-fold, and broadcast to every university and hospital on the planet. The, digital fingerprint for every.bio-reaction, from bee-stings to chemotherapy, will be stored on Zip cassettes in doctors’ surgeries everywhere.

Dr Benveniste predicts this could be the scientific breakthrough that defines the 2lst century. His peers disagree.

Nature, the world’s most prestigious Scientific magazine, published his first findings more than a decade ago, and was shocked by the hostility of the establishment. The editor later

attacked Benveniste’s research, and the French government withdrew funding.

The revolutionary fought back. Earlier this year he addressed a heavyweight Cambridge gathering grid and his professional website presents a mass of convincing evidence.

His theories developed from the discovery that diluted doses of medication could still be effective even when they were diluted down to water, with no medicine remaining. Benveniste talks of “the memory of water” though the soundbite has laid him open to rididule by skeptics who claim he is trying to make a science of homeopathy. Michael Schiff reclaims the phrase and his book unleashes a stinging rebuke of all those who want to censor scientific research until it fits their narrow minds.

THE EMERALD TABLET by Dennis William Hauck, New York, Penguin Arkana. 45Opp. $16.95.

Reviewed by Uri Geller

Sir lsac Newton who discovered the laws of gravity and motion and spectra, would work till dawn for nights on end in his locked laboratory, deciphering the 3,500 year-old secrets of alchemy. His translation of its key text, the alchemist’s Bible Called the Emerald Tablet,

is still one of the best versions available.

Hauck, who edits an e-mail digest of paranorrnal news has chosen that title, not to rework the text but to explain it and to present a masterful overview of the beginnings of science.

From the clear, inspiring definition of alchemy as a system for purifying the mind, to the aecane and mystifying details of it’s occult philosophy, Hauck has all of the information under control. The search for knowledge was allied for centuries to the quest for spiritual discovery. Hauck’s book is an urgent plea scientists to remake that link, as well as a self-help guide for anyone who wishes to usd the West’s oldest discipline to widen the horizon.

REMOTE VIEWING by Tim Rifat, London, Century. 442pp. £17.99.

My own involvement with the CIA was abruptly terminated when a military intelligence officer invited me to stop the heart of a pig with my mind. I heard the name “Yuri Andropov” in my head, and I believed the real target of Mindpower murder was to be the then-head of the KGB. I walked out, but project Stargate carried on with brilliant psychics like Major David Morehouse.

Ex-President Jimmy Carter, asked to recall the most memorrable event during his time in the White House, described how a psychic used remote viewing to find a US aircraft which had crashed in Zaire. The man “wefit into a trance and gave some latitade and longitude figures.” We focussed our satellite cameras on that point and the plane was there.”

Rifat fills two-thitds of his book with photocopies of unclassified documents testifying to the truth of his claims about Stargate – the evidence is absorbing but barely legible, so for most readers their money will be buying a short essay. That’s not enough, but while it lasts, it is gripping.

Uri Geller’s novels Dead Cold and Ella are publihed by Headline. Mind Medicine is published by Element. Visit him at www.urigeller.com.

Latest Articles

Motivational Inspirational Speaker

Motivational, inspirational, empowering compelling 'infotainment' which leaves the audience amazed, mesmerized, motivated, enthusiastic, revitalised and with a much improved positive mental attitude, state of mind & self-belief.