NEWBOLD

March 1998

INTERZONE (science fiction & fantasy)

NEWBOLD Thomas MacIntosh (1967-2024) Scientist and psychical researcher, was born at 2 Mull Terrace, Oban, Scotland, 11 September 1967, the only child of Ewart MacIntosh Newbold, a solicitor, and his wife Esther MacReady of Fort William. Ewart Newbold (1918-1999) of Telford met and married late in life, ending a bachelor existence which many acquaintances had assumed to be an immutable circumstance. Friends of his bride, a schoolteacher who at the age of 39 still lived with her parents, were no less surprised, but a still greater shock came a few months later when Esther (1927-1970) announced they were expecting a baby.

Always inclined to give thanks for his blessings, ‘Tom’ Newbold sometimes remarked: “It really is quite outrageous  that I ever did get born at all” – the way he rolled that ‘outrageous’ around his mouth typifying the West Highlands drawl he retained all his life. His grandparents had shared his outrage: Ewart’s parents were already dead by 1967 but Esther’s mother and father refused to attend the Christening or even to see the child. Reluctant to part with their daughter, despite Ewart’s good social standing and comfortable affluence, they were disgusted that a middle-aged pair of newly-weds should embark on child-rearing. Others, assuming it had been a love-match, were bewildered to see the unlikely bridegroom treating his wife, even before their baby was born, with brusque rudeness.

that I ever did get born at all” – the way he rolled that ‘outrageous’ around his mouth typifying the West Highlands drawl he retained all his life. His grandparents had shared his outrage: Ewart’s parents were already dead by 1967 but Esther’s mother and father refused to attend the Christening or even to see the child. Reluctant to part with their daughter, despite Ewart’s good social standing and comfortable affluence, they were disgusted that a middle-aged pair of newly-weds should embark on child-rearing. Others, assuming it had been a love-match, were bewildered to see the unlikely bridegroom treating his wife, even before their baby was born, with brusque rudeness.

“The truth is,” Newbold once confessed to an interviewer, “neither of my parents would have made a very satisfactory spouse to anyone. They both wanted a child, urgently, so they decided to be unsatisfactorily married. Naturally, it couldn’t last.” In fact, Newbold Senior wanted more than simply ‘a child’: he wanted a son, a son whose character he could mould and whose education dictate. “What my father wanted, really, was to be reincarnated.”

The Newbold marriage disintegrated. Esther, estranged from her family, severed from her job and living in a strange town, could not hope to withstand the withering disdain of a man who had all of Oban as his natural ally. Thomas being born, Esther was redundant, and she was made to know it. Thomas’s earliest memory was of watching a woman, his mother, as she sat in the family car in the road outside their home, eating her dinner with a plate on her lap because Ewart had banished her from the house. “I cannot recall my mother ever dressed me or fed me or taught me. It was always my father.”

Esther moved away in June 1970, and was killed in a car accident in Kings Lynn six weeks later. Her absence made  little impact on the Newbold home. Ewart, who had virtually withdrawn from legal practice two years earlier, was already deep into a teaching programme which would have daunted most bright ten-year-olds. Thomas was to learn German, French and Russian; he was to be able to read at three years, to know simple arithmetic at four, to begin on abstract mathematics at five. The child repaid constant attention and instruction with an earnest vigour which soon saw him overshooting targets – he read and memorised entire passages at a reading; he performed calculations in his head as quickly as they were spoken; he displayed an uncanny ability, which stayed with him all his life, to grasp both a mathematical law and its logical extensions before the latter had been explained. “Show me a rule of thumb,” he said without boasting, “and I can see all the fingers too.”

little impact on the Newbold home. Ewart, who had virtually withdrawn from legal practice two years earlier, was already deep into a teaching programme which would have daunted most bright ten-year-olds. Thomas was to learn German, French and Russian; he was to be able to read at three years, to know simple arithmetic at four, to begin on abstract mathematics at five. The child repaid constant attention and instruction with an earnest vigour which soon saw him overshooting targets – he read and memorised entire passages at a reading; he performed calculations in his head as quickly as they were spoken; he displayed an uncanny ability, which stayed with him all his life, to grasp both a mathematical law and its logical extensions before the latter had been explained. “Show me a rule of thumb,” he said without boasting, “and I can see all the fingers too.”

It quickly became plain to Ewart Newbold that his protegé was going to outshine him – was too brilliant, in fact, for a career in the law. The slow procession of legal niceties would suffocate him. The halls of academe were his natural abode – but under which roof? Ewart, who had studied law at Durham, was ascetic to the point of masochism, rising before dawn even on the longest days of summer and denying himself food unless he achieved daily objectives. Thomas accepted the regime. But as even a child, he possessed an aesthete’s imagination. Reading voraciously, he discovered a love of stories, rooting them out of encyclopedias and history books when his father banned fiction from the home. He insisted on being taken to concerts, beginning a life-long passion for Beethoven at seven, and though he was never permitted to learn an instrument he always had perfect pitch, explaining that each note in an octave was as definite to him as each colour in a spectrum.

Add to these precocious abilities a talent for asking unanswerable questions, and it was clear by 1974, when Thomas sat his first General Certificate exams, that law was not the only subject too dry for his tinderbox mind. He might also burn out of control in chemistry or mathematics – though he excelled in these subjects, passing A-levels at Grade A aged nine. Before his tenth birthday, he had devoured all the private tutelage his father could provide. He became the youngest under-graduate ever at Oxford. The course was physics, the college Brasenose and the public interest phenomenal. The austere Newbolds became an overnight sensation, less celebrities than media freaks. They walked together, sat in lectures and tutorials together, worked side by side and ate alone together. The father spoke of his son almost as a physical piece of himself, like a third arm: it was always, “We are studying, we are excelling.”

Ewart attempted to fend off media interference but long absence from the wider world had dulled his judgement; remaining suspicious of the university establishment, which was keen to shield its pre-pubertal pupil, the father preferred to put his trust in journalists and fixers who invariably betrayed him. Thomas Newbold was never allowed to sink from view, for his father’s unguarded comments and ill-advised interviews gave the press a steady diet of fresh information. By the time he achieved First Class Honours in 1979 everything in the twelve-year-old’s life from breakfast cereals to bedtime routines had been divulged to reporters. The student himself, wise beyond his years, chose his public words carefully. But the strains in his relationship with his father were already becoming apparent. Newbold later identified his own longing for respect as crucial – respect as a student from his older peers and respect as an individual from his father. Most probably it was also at this time that he learned his grand secret – a secret which the world would discover only after his death.

In 1980 Thomas, barely a teenager, applied to have himself made a ward of court. The plan was his own – he would live on campus, with the support of tutors, while he studied for his doctorate and taught under-graduates. His father would be allowed access to him only under supervision and only when both the child and the tutors agreed. This was a hard blow to Ewart, and quite unexpected, but Thomas saw that a clean, ruthless break was the only chance to bypass the bitter squabbling which was already their main form of discourse. “Our relationship was poisoning itself. I had to bang open some doors and let the air clear.”

Ewart Newbold returned to Oban and shut himself indoors. He had no phone, no television and took no newspapers. His curtains were always drawn. He paid his bills, took in his milk and once a month walked to the local stores to restock his cupboards; otherwise, the world had no sign that he was alive.

The prodigy thrived. Despite newspaper columnists’ fears that he would spin into dissolution, in a whirlpool of parties and drugs and sex and sects, Newbold simply continued to apply his rapacious mind to physics. He was particularly drawn to the borderline with philosophy, where sub-atomic particles allowed time to split into similtaneous universes and extra dimensions lay curled up and unseen. The vigour of his studies allowed little space for loneliness, but he seemed easily to replace his father’s companionship with casual friendships. An articulate but not yet mesmeric speaker, Newbold had an infinite capacity for listening, which guaranteed him a lifelong supply of staunchly loyal comrades. As a teenager he rarely opened up his own heart, or indeed showed that the emotional outpourings which he attentively endured from friends really touched him. “I stared at other people’s feelings,” he later said, “and wondered what on earth I felt myself.”

A move to Stanford, CA, followed in 1988, where his work at the Linear Acceleration Center was combined with a senior lecturing rôle at the University of California. Many predicted a Nobel Prize would drop into his lap for his particle annihilation research (it did not; Newbold did not win the prize until 2001 and then, uniquely, again in 2007). What no-one expected was that his many-coloured electronic images of antiproton collisions with protons to create Newbold Stars would feature as posters on a million students’ walls. Asked what fired his urge to experiment with the building blocks of matter, he answered: “Nothing is what it seems, nobody and nothing. I want to discover the secret biology of the universe.”

A professorship in 1991 was accompanied by the physics chair at Hamburg, conveniently close to the Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron accelerator (DESY). Newbold was the first Western nuclear scientist to inspect the work of the Institute for High Energy Physics in Beijing. In 1995 he returned to America, as Senior Principal Scientist at the Cornell Electron Storage Ring (CESR) at New York’s Cornell University. At this stage he discovered an aptitude for speaking to camera and, accepting his celebrity for the first time, began appearing on television. “You’ve got to talk when a camera’s around,” he explained. “A camera never breaks the ice – it waits for you. Just sits there, waiting to hear something.” The remark revealed as much about his approach to human contacts as televisual ones. But his modesty belied his real skill at taming complex subjects so viewers would not fear them. “Everyone’s got a particle accelerator in their home,” he famously told a press conference at CESR. “It’s called a TV tube. All I do is play around with big televisions.” He liked to remind colleagues that Sir William Crookes, who in 1879 began the study of glowing gases within electrically-charged glass tubes, was also a founder of the Society for Psychical Research.

There had been meetings with his father during the past decade, but never the hoped-for reunion. “He’s still living in the past,” Newbold confided to a friend at CESR. “I can’t travel back in time to fetch him. Not even in a particle accelerator – not yet. He has to make his own way forwards to Now.” A brush with death in 1997 gave urgency to his desire to repair the breach: Newbold was driving at around 110kph on the interstate south of New York when a beam of red light blinded him. He lost control of the car and struck the central reservation before bouncing back into the overtaking lane. By a miracle, the heavy traffic was able to steer round him as he pointed his car across four streams of vehicles and onto the embankment. The light had been fired from a hand-held laser, probably built into a key-ring or a blackboard pointer and aimed from a bridge or a passing car. Newbold accepted it was a random attack; although newspaper reports hinted at criminal intent by jealous rivals or a celebrity stalker, the police were convinced he was the unlucky victim of a juvenile who’d discovered a new form of vandalism. He escaped injury, but for the rest of his life he was colourblind.

Typically, Newbold turned his experience to the benefit of science. Dismantling a laser keyring to study its mechanics, he noticed two quartz crystals which focussed the beam by vibrating minutely like motorized mirrors. He began to investigate the energy potential of crystals, theorizing they might serve to amplify or even harness the forces unleashed when particles collided. He also became an enthusiast for the healing powers of crystals, a quirk which earned him much hard ribbing from colleagues. With his usual openness, he neither hid his belief in the mystical properties of crystals nor brooded on the mockery of other scientists.

He credited crystal power with healing the father/son bond. After weeks of intense meditation, which he described as “firing particles of love across the Atlantic from an accelerator crystal,” Professor Newbold received a summons from Oban, to a 70th birthday party. “It wasn’t the wildest party,” he recalled – “just me and my dad. Like the old days. But he’d acquired a stray cat, and that rather lightened up proceedings.”

The reunion was not fated to last. Within a year, Ewart Newbold was dead from prostate cancer, unaware until the last three weeks of his life there was anything wrong with him. Newbold had returned to New York after a week in Scotland and, although the possibilty that his father might join him in America had been mentioned, they never saw each other again. Newbold said he was woken at 6:11 on January 4, 1999, by his father’s voice saying, “I’ve come to join you in your work, Thomas.” At this moment, 2,000 miles away on the north-west coast of the British Isles, Ewart Newbold was dying. Thomas later called this, “the pivotal instant of my existence.”

The profound shock of a telepathic communication from his father’s spirit was amplified, during the months that followed, by repeated messages. Newbold’s first attempt to confide in a friend was brushed aside with embarrassment, and he quickly learned that death’s social taboo extended to every subject it touched, from grief to spiritualism. Initially, the scientist in Newbold explained the perception of his father’s voice in his ear as a delusion of grief, perhaps made all the stronger by the fact it was the only serious symptom of mourning he experienced. “I took my father’s death pretty well, on the whole,” he commented. “It seems he took it rather less well.” The voice commented on the people Newbold met, the methods of his work and, most forcefully, on his daily habits. A preference for Apple Macs over IBM-compatibles in the CESR press-room might exact no more than an aside from the disembodied mentor, but Newbold’s habit of listening to Beethoven or Brahms late in the evening while sipping an island malt could provoke a full-blown rant. Newbold rationalised he felt guilt at his father’s lonely death, a guilt which, in manifesting itself as aural hallucinations, enabled the grieving son to despise himself whenever he failed to maintain Ewart’s standards of austerity.

Gradually, the scientist Newbold was displaced by the philosopher Newbold. Could this actually be a case of haunting, even of possession? “One morning I turned the question around: was there any evidence to suggest this was not genuinely my father? And at that point I realised I had a working hypothesis, which I either could or could not disprove.” Whether or not Ewart Newbold was real, the son found he was no more able to live with his father than he had been at 13. Fearing the voice could drive him out of his wits if he continued to tolerate it by himself, Newbold took two steps: he consulted a medium and he moved into a large apartment at Cornell with a pair of colleagues. The medium was Dr Alex Mornay; the colleagues were Jacob and Vanessa Kru-Starling.

Mornay’s practice, a side-line to her work as a hearing specialist at the university medical centre, was not conducted for profit but patients were expected to make a sizeable donation to charity before being considered for treatment. This donation, naturally, was non-returnable. Newbold, in paying $5,000 to the Princess Diana Memorial Fund, was demonstrating considerable faith in his hypothesis that Ewart spoke to him from beyond the veil. His faith was rewarded, rapidly. At the first sitting Mornay, a materialisation medium, became stricken by a trance almost as soon as Newbold entered her chambers. He noted she had no time to dim lights, attempt distractions or engage hidden machinary. He also noted that, standing on his left side and partly obscured by wall heater – as though standing actually in the wall – was his father. The body had a vaporous inconstancy but the eyes and mouth were vivid. The pupils fixed unblinkingly on Newbold, so that it took all his strength to return the gaze. The mouth was moving but, inexplicably, the voice did not come either from the wraith or directly within Newbold’s ear; instead, it was spoken by Dr Mornay, who had fallen back into a chair and was seized with rigid tremors which caused her legs and arms to extend and twitch. Confronted physically by his father, Newbold found himself better able to answer the voice, and a furious dialogue quickly developed which later he estimated had endured for an hour. When the spirit vanished, Dr Mornay was in a state of exhaustion and dehydration, and in fact passed that night under surveillance in hospital. The voice, however, did not obtrude again, which Newbold took to be the final proof of its reality.

“I had to convince my father he was truly dead. He did not know it. He was like a man dreaming, aware that nothing is real but unaware this state of affairs is not normal,” Newbold wrote in his autobiography, Vital Signs (2023). My life was more like a nightmare to him, because he wanted to control it and he couldn’t. It had been that way ever since I graduated and our one meeting, just before he died, had not been enough to reconcile him to this unacceptable fact. So his spirit carried on, struggling with its errant son. And thanks to the generosity of Alex Mornay, who for short periods was able to allow spirits to subexist through her vital energy, my father and I had another meeting. This time, he faced some difficult truths. I think when he had made the immense mental leaps that permitted him to say, “I have passed over,” the other facts followed meekly. He became reconciled. I look forward to meeting him, in the beyond, knowing our differences have been wiped away.”

Newbold the scientist, anxious not to be discarded, started to gain ground rapidly on Newbold the philosopher. A theory of materialisation was propounded that would lay the groundwork for his momentous second Nobel Prize. The theory drew on two main sources: the experiences of Dr Mornay and the CESR research into crystals as amplifiers which was about to revolutionise particle physics.

Dr Mornay’s belief in the endocrine glands as points of intersection for a human being’s biological and astral bodies was adopted by Newbold, though tempered by later discoveries. The glands, otherwise known as the seven chakras in Hinduism, occur at the crown of the head, the brow of the face, the throat, the heart, the solar plexus, the sacral (close to the sexual organs) and the base of the spine. According to Dr Mornay, a person’s spirit saturated its body and flowed into the flesh-and-blood system through the glands. Misalignment occured when trauma or depression displaced the astral form, usually to the right. To a psychic, Newbold’s spirit could be seen quite luminously, projecting from his right side. Its colour was a faint, glassy blue, indicating the trauma was an old one, probably dating to puberty. The effect of this displacement was to leave Newbold’s left side unoccupied, providing an easy platform to a spirit recently deprived of its own body yet unaware that it should be passing on the the next plane of life. The phenomenon of body displacement and spirit possession was fairly common in severely depressed patients or those suffering nervous breakdowns; the mental illness superceded the possession, which was then dismissed by rational doctors as a hallucinatory symptom of the sick mind.

The remedy for astral dissynchrony was meditation, a discipline which Newbold applied vigorously. His favourite technique, he enjoyed telling friends, was to count his thoughts: sitting upright on a comfortable chair, clasping a rock crystal between his fingertips, he would observe each thought as it entered his head, number it and dismiss it. “If you don’t try to chase them, it’s surprising how easily they slip off,” he confided. “Embarrassment at their own banality, I shouldn’t wonder.” But what tickled him most was their infrequency – sometimes as few as three thoughts in the space of a minute. “Thank God for a decent education,” he loved to say, “because it’s plain there’s nothing very brilliant about the grey matter itself.”

The Nobel committee disagreed, and two years after his father’s death it awarded him the Physics Prize for his extraordinary particle energiser – the Ewart Accelerator, named after the man who gave him his education. The accelerator’s dramatic design, marrying 1950s comic-book science-fiction to commonplace technology, captured the public imagination, with the result that sub-atomic physics became as popular as cosmology had been a decade earlier. Even Hollywood got in on the act, prompting Newbold to quip on a live prime-time chat-show: “That film gets the facts and the physics equally f-f-fuddled!” Countless newspaper graphics tackled the physics, showing a cutaway of a glass tube forming part of a ring 30 kilometres long. Below the ring at two points, as far distant as possible, were powerful electro-magnets. An electric pulse generated a magnetic field and in doing so created an opposite electro-magnetic zone around two pieces of quartz within the tube. The conflicting fields forced the objects apart; since the coils were fixed, the crystals were bound to float. This natural reaction, well known to science since the 19th century, had the bizarre appearance of a conjuring trick and contributed hugely to the public fascination with particle guns. A lateral magnetic field, applied inconstantly, caused the crystals to spin in the almost frictionless vacuum. Any nuclear particle discharged between those rapidly rotating chips of quartz was subject to an overwhelming energy increase.

Particle physics defines sub-atomic masses in terms of potential energy, which increases in relation to velocity. An electron gains energy to the value of one electron volt (eV) when it accelerates through an electric potential of a single volt. Thousands of electron volts (KeV), or millions (MeV), or thousands of millions (GeV), or millions of millions (TeV) are the usual gauges. When we consider an electron’s mass (where, in the equation e=mc2, the velocity of light is equal to 1) can be expressed as 0.51MeV and the average human’s mass as 4×1031, we begin to appreciate Einstein’s remark that detecting particles is like “shooting sparrows in the dark”.

Before the Ewart Accelerator, the greatest energy potentials achieved were around 20 TeV. The new technology multiplied that ten-fold. For the first time, the physicists at CESR were able to smash protons and anti-protons together so hard that the quarks and leptons flung out in the explosion unravelled themselves. The hidden dimensions, prefigured by mathematical theory for nearly 20 years but never observed, radiated measurable effects. Seven additional dimensions of space and a second dimension of time – Newbold’s Hypertime – became observable. Every kind of thinking about the universe was revolutionised.

Newbold had continued to live with the Kru-Starlings, partly because the arrangement afforded them the luxury of discussing confidentially the momentous CESR experiments. Media reports inevitably put an ugly interpretation on the relationship, prompting an angry letter to the New York Times in February 2003, signed by all three, denying a ménage a trois. There was another consideration for Newbold: Vanessa Kru-Starling exhibited sporadic mental disorders which he believed were rooted in spirit possession. A violent upheaval from her family, followed by miscarriages and compounded by an often stormy mariage to the wilfully extroverted Jacob Kru, had deeply unsettled her psyche. Short incidents of insanity, sometimes benign, sometimes not, had begun to occur regularly. By teaching her to meditate, Newbold hoped to realign her astral body. Crystals naturally played a part, and on March 31, 2003, he assembled the skeleton of a Ewart Accelerator in the sitting-room of their apartment. While he was calibrating the lateral spin, Vanessa Kru-Starling suffered an epileptic fit from which she emerged, as had happened before, with a different personality, speaking in a rapid, grating voice and an unknown language. The fit was likely to pass quickly, but Jacob Kru-Starling recognised the condition as one in which his wife had previously attempted to injure herself. Seeing large crystals in her fists and fearing she might use them as weapons against herself, he seized her wrists. A struggle ensued, with Vanessa using almost demonic strength to force her husband to the floor. Newbold, chronically ill-suited to any physical intervention, began talking urgently but calmly to the personality occupying Vanessa’s body, and was suddenly startled to be answered from the other side of the room. A hunched figure, glaring furiously from under a green felt hat, crouched beside a book-case.

Glancing back at Vanessa, Newbold saw she was unconscious. Her body lay in a direct line from the creature, through the Accelerator. The spinning quartz, he instantly theorised, had projected the spirit out of Vanessa, drawing no more energy than she usually spent in harbouring it but amplifying the force, so greatly that a material body was formed.

The theory proved true. Catching a single strand of spirit energy between the whirling crystals, his device had unravelled the parasite body from Vanessa like a loop of wool can unthread a jumper – and then energised it to the point where it became self-supporting. Questioning the weird creature in the Kru-Starling’s apartment availed little, though a tape-recording of the end of the incident, made by Jacob, suggest the sprite was speaking an antique form of Gaelic. How it had chosen Vanessa was never known, but it was woken up, or frightened, enough not to return when the Accelerator was powered down. Without fully grasping the enormity of what he had created, Newbold spent the rest of the night completing Vanessa’s cure. The experiment had served to confirm his belief in spirit possession and the afterlife, and he did not think at first of the impact it would have on a sceptical world. Instead, he focussed on the other personalities revealed by Vanessa during her fits and, using meditation and hypnosis, coaxed out each of them. The Accelerator projected six more spirits from her body; two appeared malevolent, one was dangerously confused and three were benign – one being the spirit of her grandmother, who claimed she had protected Vanessa against the other occupiers and who was glad to return to the spirit world now her job was done.

Science was blown apart. For the first time, here was an experiment which could be conducted in a laboratory, by any trained operator, with any number of observers using any manner of recording equipment. Even individual experiments could be repeated, since a spirit once drawn out could often be persuaded back into the host human. While atheists and opponents of psychic research bayed impotently, a plethora of related experiments began, until it seemed every pysychological institute in every city around the world was conducting spirit investigations with Ewart Spirit Accelerators (ESA). Practised mediums were eager to join the tests, entering trance states to invite personalities from the past into their bodies and then allowing the visitors to be materialised through the crystals. Many spirits, initially bewildered to find themselves earthbound and corporeal, reacted with delight to the experiments, answering questions and discoursing on the afterlife with the intelligence, wit or wisdom which had been their characteristic while alive. Four days after the Kru-Starling revelation, an ESA materialised Albert Einstein in a Zurich laboratory who proceeded to talk with gusto about relativity in the next world. Such undreamed-of conversations became the sole pursuit of television stations, whose bosses were quickly disappointed to find that spirits could not be commanded to appear on their shows and were indifferent to any cash offers. Still, thousands of personalities, particularly those who had not been long dead or who had died unexpectedly and were still coming through the trauma of their own demise, were compliant. Monroe discussed her own death calmly during a materialisation staged at the White House; a painfully sad John Lennon appeared on British television; Gandhi spoke to worshipping millions in India, and offered to broker a lasting Middle East peace; Churchill confronted Hitler at a psychic conference in Moscow; Oscar Wilde, in three sittings, dictated a novel which had haunted him for a century; Dickens embarked on a speaking tour of America, declaring he was delighted to shake off the dullness of eternity; Evita returned constantly to the Argentine, where fresh miracles were wrought every day in her image; Nixon, burdened by lies, went on NBC to confess; JFK fingered his killers; John Wayne declared he would run for president (but was rapidly outgunned by the senate, who passed a law forbidding dead people to run for office).

Thomas Newbold, who overturned the weight of sceptical prejudice with a single experiment, was honoured by every nation, in every way imaginable, and at the same time attempted to shrink from public life. His great concern was physics, and he spent the rest of his life attempting to demonstrate how the afterlife could exist within the hidden dimensions revealed by his particle collisions. His theories were often convincing, but never proven – a task which, he accepted in his final years on earth, would be completed by younger scientists. Or perhaps, if permanent stabilisers could be developed for the ESA, by older ones. Even by Newbold himself.

Thomas Newbold was dark-haired and darker-eyed, with his mother’s light skin and his father’s strong bones. His ranging physique and delicate movements gave him a physical beauty of which he was patently unaware. He had many true friends but professed on several occasions that he had never had a sexual experience and never expected to. Despite this, he married Vanessa Starling in 2016, more than a decade after the collapse of her marriage to Jacob Kru. The union was short-lived, dissolved by mutual agreement eight months later. In 2021 Newbold was diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer and given six weeks to live. His regimen of meditation plus Beethoven with whisky prolonged this to three years. Refusing to be nursed, even during the final weeks, he said he looked forward to dying, so he could meet Beethoven, who was steadfastly deaf to summonses by mediums. During the last months he was comforted by a series of meetings, through the ESA, with both his mother and his father.

The greatest mystery of his life was uncovered only at his autopsy. Having left his body to medical science, he must have been certain of this ultimate revelation – that Thomas Newbold was in fact a woman.

(Sources: Thomas Newbold, Vital Signs, pub. Headline 2024; Newbold: A Life Extraordinary, by Levi Schultz, pub. Penguin 2026; Dispatches in the Times and others, April 2024; private information; personal knowledge, including interviews with Newbold via ESA, 2029-2033.)

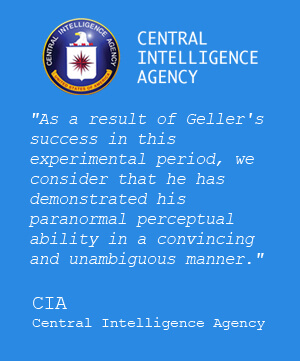

URI GELLER

Published 2034.

INTERZONE (science fiction & fantasy)

Latest Articles

Motivational Inspirational Speaker

Motivational, inspirational, empowering compelling 'infotainment' which leaves the audience amazed, mesmerized, motivated, enthusiastic, revitalised and with a much improved positive mental attitude, state of mind & self-belief.